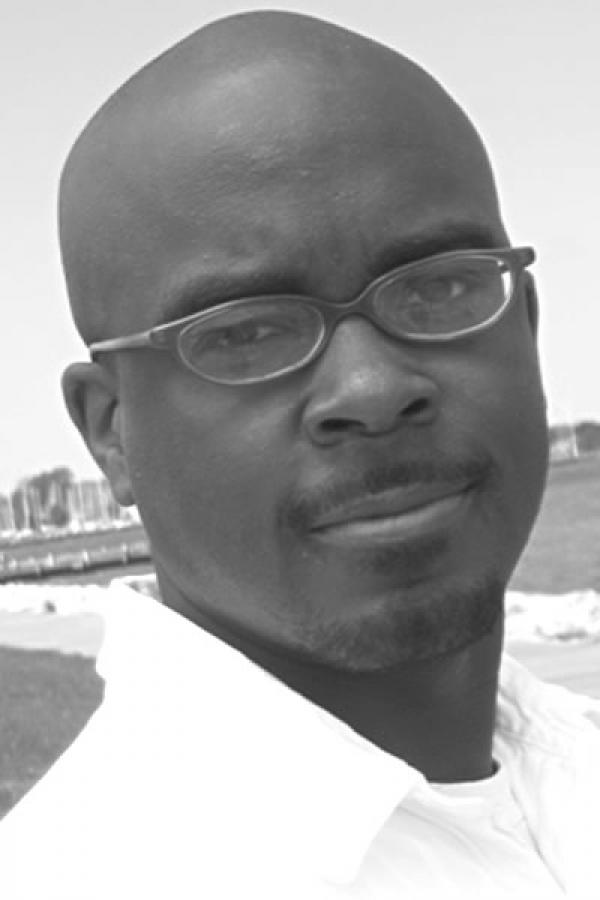

Ravi Howard

Photo by Laura Howard

Bio

Ravi Howard published his debut novel, Like Trees, Walking in March of 2007. The book gives a fictionalized account of a true story, the 1981 lynching of a black teenager in Mobile, Alabama. He graduated from Howard University in 1996 with a BA in journalism. He completed an MFA in creative writing at the University of Virginia in 2001. He has received fellowships and awards from the Hurston-Wright Foundation, Bread Loaf Writers' Conference, and the New Jersey Council on the Arts. He is currently on the faculty of the brief-residency MFA program at Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky. Howard's work has appeared in Callaloo and Massachusetts Review, and he has recorded commentary for NPR's All Things Considered. He currently lives in Mobile, Alabama with his wife.

Author's Statement

While the writing process takes authors to internal places, for many of us the path also requires external journeys. While working on my first novel, I lived in New Jersey and Maryland. I made several trips to Alabama to research the novel. I benefited from walking the same streets my characters did, moving in their footsteps and their communities. However, traveling gets expensive in a hurry. As valuable as the experience can be, the financial strain can put future travel out of reach.

With the generous aid of the NEA, the travel and research required to complete my second novel will be possible. The book, in part, follows the life of a journeyman musician, and I want to see some of the places he did. I hope to gather the kind of first-person research that can give texture to historical moments. Thanks to the fellowship, I can gain that street-level experience and use it to strengthen the work.

From the novel Like Trees, Walking

When the phone rang so early in the morning, it oftentimes meant somebody was dead. An elderly person had passed in the night. A Friday night traffic fatality. The families of deceased would set about the task of notifying family and friends, and somewhere among the sad litany of phone calls, they dialed our number.

As a child, I would answer the phone in the family room during my morning cartoons. Our parents had instructed us on the phone etiquette they expected at all times, especially when the caller could be a grieving family member. Turn down the television or radio. Speak clearly and mannerly. It had become a conditioned response, because there was no telling who was on the other end.

A second ring.

The sound echoed through the green plastic casing of the rotary phone mounted next to the laminated list of emergency numbers, just below the calendar that carried our picture.

The phone rang once more.

Eventually these calls would be mine alone. I had always listened to the reassuring tone my father took: Earnest without condescension. Listening more than speaking. Choosing the right words and knowing exactly when to say them. The proper timber of the voice. By then I was a senior in high school, and I had worked more funerals than I cared to count. Had fielded just as many phone calls. Despite the preparation, I had not yet mastered the fortitude that my father exuded, the calm that his voice carried no matter who was the subject of the call.

"Nobody needs your grief on top of their own," he had said many times.

Just before the fourth ring, I answered.

"Deacon Residence. Roy speaking."

It was Sgt. Kincaid, whose voice was familiar from our church choir, the smooth tenor that would lead songs. Although he had that rock-steady tone expected of police officers, on that morning his voice was shaking.

"Roy, I - I need to speak to your daddy."

"Just a second, I'll get him -"

"Roy," my father said.

I had assumed I was the only one awake. As though he had heard his name being called in his sleep, my father stood behind me clad in a bathrobe and pajamas reaching for the phone. While he spoke to Sgt. Kincaid, I pretended not to listen while I sprayed the starch on my collar. Mr. Kincaid's voice spilled out of the phone, but the words were too distorted to make any sense of. As Daddy looked out the window, I tried to read his face but got nothing.

Out of habit, my father would run his fingers along the carvings in the gopher wood table while he reassured the person on the phone, but this time his hands were still. He said nothing. The only sounds I heard were the cryptic hum of Sgt. Kincaid, and the whisper of the iron making its steam, water droplets sizzling against the steel before they turned to vapor. I rested the iron, and pulled the left sleeve tight across the board.

"Is Paul all right?"

I heard my brother's name just as I reached for the iron. Instead of the plastic handle, my fingers touched the face, burning a red line clear across my palm. I swore in silence, waiting to find out what was happening.

"Where is he now?"

The toaster in the kitchen coughed up my slices, but my hunger was already gone. In its place came the resulting uneasiness of hearing my brother's name in the early morning phone calls that in our house only meant one thing. After a heavy silence, my father's fingers loosened, and he mouthed a Thank God as he collected himself.

"We'll be there in ten minutes," he said, just before he hung up the phone.

"We have to go see about your brother," he said.

"What's wrong?"

"Michael Donald was lynched last night," he said. "Your brother found the body."